Nowadays, latex has again become popular as an alternative to conventional foam. Twenty years ago, this material had almost completely disappeared from the market due to a fierce price battle associated with material savings and constantly worsening product quality. Even today, many companies that fabricate comfort items are reluctant to using this material. In the last couple of years, however, there has been a lot of movement on the market with respect to latex whose image has been slowly improving. As a result, it is again being used in a number of comfort products.

Production of latex (Talalay latex and Dunlop latex)

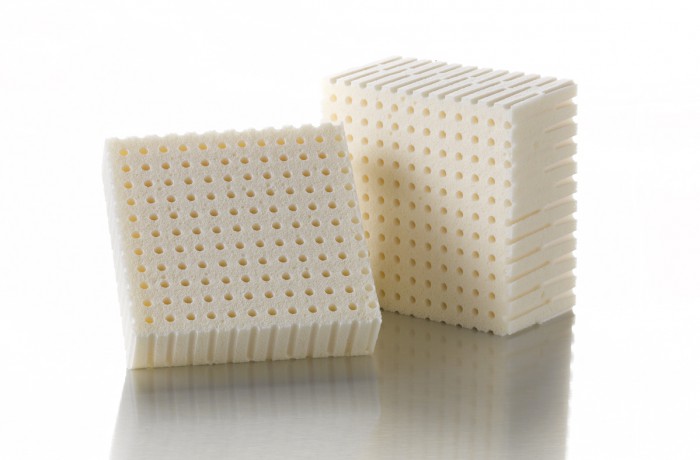

Two different types of latex can be distinguished: (conventional) Dunlop latex and Talalay latex. The latter requires a sophisticated production process but provides unrivalled comfort characteristics. To produce this material, a latex blend is cast into a vacuum mould exposed to below-zero temperatures. As a result, the material is evenly spread across the mould whilst retaining its uniform cell structure. The mould is then heated, and vulcanisation starts. This process cross-links long-chain rubber molecules to lend a “soft” feel and unrivalled breathability to the material. By contrast, the Dunlop latex production process does not use a vacuum or cooled casting mould, which is why the cell structure is more closed. Either of these latex materials is available as a blend of synthetic and natural rubber or as a 100% natural rubber variety.